Gastronomy of the Missions in Sonora and Arizona

INTRODUCTION

“The Spanish pepper, which is called chile in America, is abundantly grown in Sonora, as it is in all of New Spain, because it is the Spaniards’ favorite spice for seasoning their meat and lenten dishes....Even when the fruit is not yet ripe the Spaniards mouth water for it. When it is still green they roast it slightly on hot embers so that they can remove the outer skin which is supposed to be much too hot. They prepare the fruit with vinegar and olive oil, or, since olive oil is so scarce and expensive, only with salt and vinegar and eat it with such appetite that their mouths froth and tears come to their eyes. They are fonder of this food than we are of the finest garden lettuce. The amusing thing about it is that they proclaim it to be a very healthful and cooling dish.”

These are the words of the Jesuit missionary Ignaz Pfefferkorn, taken from his book, Sonora: A Description of a Province. The German author spent eleven years in Sonora and Arizona among Pima, Opata and Eudeve speaking peoples at the frontier missions of Atil, Guevavi and Cucurpe before he was eventually expelled from New Spain by order of the Spanish government in 1767. Fortunately for the historical record, Father Pfefferkorn and others preserved the memories of their one-of-a-kind experience as foreigners living in the eighteenth-century Sonoran Desert amongst native peoples and Spanish colonial society by putting them to writing. Through these primary sources the world of missions comes alive, including this colorful culinary anecdote of how the conquerors of Mexico had been conquered by the taste of chile and their ravishing appetite for the piquant delicacy. This text looks through the lens of these frontier Black Robes and some of their contemporaries to spotlight these author’s perceptions on the indigenous foundation of Sonoran cuisine, the successes and failures of the introduced Old World foods and gain insight on this period of syncretism between those traditions to make the case that the missions of Sonora and Arizona served as the early kitchen laboratories for the genesis of Sonoran cuisine.

Gastronomy is defined as “the art or science of good eating,” according to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary. There is also a popular proverb in the United States that states: “the way to a person’s heart is through their stomach.” In other words, human motivation is guided not only by sustaining nutrition but also gastronomy and its incredible power to change hearts. The purpose of this work is to demonstrate how implementation of this proverb into practice was leveraged during the encounter between the native peoples of Sonora and Arizona and the Jesuits in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Its goal is to showcase how gastronomy and culinary diplomacy played a fundamental role in the mission history of northwestern Mexico by highlighting what the Jesuit documentary record states on the food culture and economy of Sonora during this time when two cultures met, coexisted and shared foodways.

THE INDIGENOUS FOUNDATION OF SONORAN CUISINE

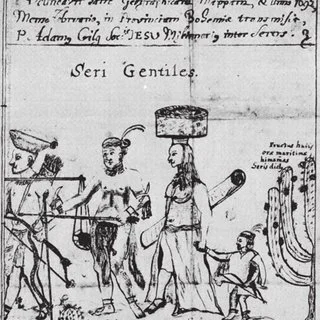

Drawings of Ignacio Tirsch. Jesuit Missionary in Northwestern New Spain, 1760s

To understand the cuisine of Sonora and its later development in the missions it is essential to learn about the land, its climate and the cultures of its native peoples. To provide a very brief background, University of Texas geographer Robert West put forth the theory of understanding the state of Sonora by way of what he called its dual geographical and historical personalities. According to this cultural landscape theory, by bisecting the state from north to south with an imaginary line, one can better understand the region from not only a geographical perspective but a historical one. In this approach, one Sonora is its western half, an area characterized geographically by a flat coastal plain leading up the and one of the longest coastlines of any state of Mexico. These are the traditional lands of the Comcaac, Cucupa, Tohono and Hia-Ced O’odham and in the coastal and riverine south, the Yaqui and Mayo peoples. While the other half of Sonora is eastern Sonora, the Sierra Madre zone, known for its mineral rich, north-south running mountain ranges divided by multiple river valleys. These river valleys and sierras are the traditional lands of the Opata, Eudeve, Pima, Guarijio,Tarahumara, Apache, and Kikapu peoples and later would be the focus of Spanish mission and mining activity in the colonial period. Not only geography but also the climate of the Sonoran Desert impacted and shaped Indigenous foodways.

CLIMATE

Climate in these dual personalities of Sonora played a critical role in the annual maturation and desert adaptation of Indigenous agriculture and the abundance of wild foods. Weather’s significance for the successful maturation of native crops can be seen on the reliance of a critical fifth season in the Sonoran Desert, the monsoon season, as well as winter showers known as equipatas, which would prove consequential for the later introduction of wheat. The Indigenous peoples' awareness of this pattern, its often precarious reliability and its importance to subsistence is clear in the tradition of maintaining alternative plantings irrigated rather than only rain-fed in case of drought or other agricultural disasters like early frosts. The native peoples of the area which now comprises the modern states of Sonora and Arizona were incredibly diverse from their languages to their subsistence patterns. However, these diverse peoples often shared similarities in cuisine on the basis of what was available in the Sonoran Desert’s natural pantry as well as shared agricultural products and techniques developed in the fertile river valley drainages of the Sierra Madre mountains and beyond. Many of these wild foods and indigenous agricultural practices were uniquely adapted to and influenced by the region’s geography and climate as well as domestication processes and also continued to be consumed in the later settings of missions.

THE SONORAN PANTRY

PORRIDGES

The Jesuit chronicles offer a documentary window into the native pantry of Sonora and the pre-Hispanic ethnobotanical traditions of certain wild ingredients. Approaching this subject by wild ingredient, excerpts from the Jesuit chronicles will be shared on the native mesquite tree, pitahaya fruit and elderberries. Some of the traditional first meals of the day in Sonora have their origins in native cuisine and utilization of the region’s wild foods. Atol de pechita and atol de tapiro are two examples of traditional sweet porridge-like dishes still consumed in the river valley communities, like the Altar, of Sonora today. Their origins date back to the pre Hispanic native communities or rancherias and later became staples of the missions situated along waterways lined and shaded not only by giant cottonwoods but by dense bosques of mesquite and Mexican elderberry (Sambucus mexicana). Harvests of the leguminous beans ground into mesquite meal (pechita) and the purple elderberries coincided with their addition to enhance the flavor of grain based (often corn or wheat) porridge dish known as atole.

MESQUITE

Not only an excellent wild food as in atol de pechita, but also a marvelous multipurpose resource, the mesquite tree is a key ingredient to the native food culture of Sonora. The trees’ harvest seasons and dynamic qualities were explained by a contemporary colleague of Pfefferkorn, Juan Nentvig in his work Rudo Ensayo:

“The mezquite tree [Prosopis juliflora], quiot in Opata, is found throughout the hot and temperate regions of the province. The natives harvest these trees twice a year, the first being in April when the pods are tender. They are boiled and dried for later use in their stews. The second harvest is in June when the pods, called péchitas, have ripened. Some are eaten at the time of picking, but the greater portion is saved to make atole and other dishes. The mezquite gives off an edible gum, quio-chucat in Opata, similar to the gum or jelly of Michoacán. It also gives off quio-possore, a sap employed in the treatment of sores. Quio-possore is used in place of blue vitriol.”

The author, another German speaker, Padre Nentvig was born in what is now Kłodzko, Poland, produced an extraordinary map of the region (which you can find in the museum of Tumacacori NHP) and eventually faced expulsion in 1767. The Jesuit chronicler died along the forced march back to Spain for imprisonment near Izlan, Nayarit. The leveraging of mesquite tree for cooking traditional Sonoran cuisine goes beyond just the edible pod and other uses described by Nentvig, it is also a quintessential regional cooking fuel and flavoring agent - whether wood fired or mesquite carbon- and was quickly adopted by the Jesuits and Spanish colonial society and continues to be preferred to this day. The use of this wood was no doubt practical in taking advantage of it as an abundant local resource for cooking, however what is also important to remember is the distinct flavor imparted by this wood as an irreplaceable and sometimes overlooked quality of Sonoran cuisine.

PITHAYA

Another important endemic food source of the region comes from another forest - the Sonoran columnar cactus forest - and is called pitahaya. It is the fruit of the Organ Pipe Cactus, a key ingredient of the seasonal Sonoran pantry of summer that even evidently became a favorite of the German Jesuit:

“With even greater appetite, the Sonoran eats tamales or cakes made from the excellent meat of the pitahayas. I must confess that these cakes are not at all to be scorned...They keep for two or three months without spoiling at all, and they can be prepared twice annually, because the pitahayas yield fruit twice a year.”

Beyond tamales, it is very likely that the pitahaya was employed as a sweet ingredient in other dishes born out of culinary experiments in the native rancherias and later in the kitchens of the missions, likely as an atole flavor. It is certain that drinks such as agua de pitahaya would have also been introduced to the Jesuits, which would have been crushed on a stone mano y metate to extract the juice of the fruit for making the refreshing beverage and even for the fermentation of wine.

The first European drawing of the Seris by Padre Adam Gilg.

Drawings of Ignacio Tirsch. Jesuit Missionary in Northwestern New Spain, 1760s

TAPIRO

Mexican elderberry was not only used as a flavor enhancement to corn porridge but like the pitahaya was also to make an alcoholic beverage which was met by disapproving push back by the Jesuits as explained by Nentvig:

“The Mexican elder [Sambucus mexicana] is a fairly common tree in both Pimerías. From its berries the Altos make a beverage so potent that those who drink it to excess get so drunk that it takes two or three days to sober up. Believing that such vice is the cause of many evils, the missionaries have tried unsuccessfully to stop the Indians from making it.” (Netvig 41)

Whether out of necessity or taste or both, many of these foods like elderberry, appear to have been quickly adopted by the frontier Spanish colonists who arrived in the region to mine, ranch and pursue other economic activities, like the harvest of pearls along the coast. One can see this acceptance of the staples of the local diet by these colonists based on the experience of Ignaz Pfefferkorn while living in Sonora who commented:

“There is little difference between the food of the Indian and that of the common Spaniard in Sonora... they get along with posole, pinole, atole, and tortillas, and they are completely satisfied if with these dishes they have a piece of dried cow-beef or beef. Mutton, chicken, and other good dishes are only for the tables of the wealthy.”

Drawings of Ignacio Tirsch. Jesuit Missionary in Northwestern New Spain, 1760s

THE JESUIT ARRIVAL

The very opening act of the Jesuit arrival into Sonora that would mark the beginning of the region’s mission era was a salvo of culinary diplomacy. A distribution of stores of grain from established Sinaloan missions to the indigenous Mayo was ordered when Padre Pedro Mendez and Captain Huraidade encountered their settlements pushing northward along the namesake river stricken by famine in 1614. The end of the century and a half Jesuit era in Sonora and Arizona occurred with their expulsion from all Spanish dominions by order of the Spanish government in 1767. This initial century and half timeline of encounter and interaction would lead to the development of the gastronomic tradition born out of experimentation between the native ingredients and traditions of the Sonoran Desert and the introduction of foreign agriculture, livestock and culinary techniques. This initial globalization of the local cuisine would take place in the missions.

Continuing north on the missionization process, the first successful entrada into what is now beyond the Yaqui River of the modern Mexican state took place by two Black Robes of the order who were unaccompanied by military escort and on invitation of the Yaqui. Crossing this important drainage river of the Sierra Madres, the Cordoban Andrés Pérez de Ribas and Sicilian Tomás Basilio were equipped with knapsacks not filled with the gunpowder and projectiles of failed prior entrada attempts by Sinoloan-based military personnel, but rather with an astonishing variety of new seeds and cuttings, external to the area. Some of these Old World seeds would flourish in their adopted home while others would be unable to acclimate to the extreme climatic circumstances of the Sonoran Desert. As early agricultural extension agents, Jesuits who take first note of this, as in the example of Nentvig who states:

“Similarly, the lands of the Opatas and the Pimas give abundant returns of lentil beans and other legumes, but garbanzos, vetches, peas, etc., do not come up to expectations except in a few areas. Beans, in some soils as those of Batuc, Mátape and Tecoripa, after two or three plantings, degenerate into a type that the natives call tépari. It is of inferior quality, lesser in nourishment and smaller in size. The same thing happens with white cabbage. After two or three plantings, especially in warmer areas, it becomes a less desirable vegetable. In colder climates, as in Bacerac, Cuquiárachi, Arizpe, and Pimería Alta, it retains its original quality longer.”

In these statements we are also witness to the central European’s prejudices and bias of presuming the tepary bean on the basis of its size was a ‘degenerate’ version rather than understanding its unique adaptations including a critical water thriftiness developed over generations of desert domestication. Jesuit missionaries like Nentvig were individuals who became accustomed to agricultural administration in the missions they founded and certainly thought in quantific terms of stretching their supplies to the furthest to be able to successfully nourish the entire mission community and to have a surplus to sell to finance the religious establishment’s other needs.

THE MISSIONS: THE KITCHEN LABORATORIES THAT GAVE BIRTH TO SONORAN CUISINE

The mission's institutional counterparts of Spanish colonization on the northern limits of New Spain also included the military posts (presidios) and mines of colonial civil society. Given the transitory nature of both the boom and bust mining communities as well as garrisoned presidio personnel often on assignments in distant locations, a vernacular cuisine did not have a chance to take root as readily in these localities as in the industrious missions which were often the first colonial outposts in the region and with communal stores of foodstuffs to experiment with. Food production and gastronomy were so important to the mission's economy that the survival of the frontier military posts and mines often depended on the missions for food and supplies which offered the most reasonable prices locally on commodity goods. This symbiotic relationship between the mining settlements and the missions, became a basis for the frontier colonial economy in the Sonoran Desert is explained by Pfefferkorn:

“Maize, wheat, beans, peas, sugar cane, and Spanish pepper were grown in all the missions. Various kinds of livestock were raised. Such supplies of tallow, molasses, jerked meat, and hides as the missionary did not need for himself and for the support of his Indians were disposed of to the Spanish miners at a very low price. This income in gold and silver the missionary sent to the steward in Mexico City along with a list of his needs. The supplies requested were sent to the missionary in good order the following year. The missionary expended least of all on his personal needs. Most was used for the needs of his Indians and for church ornaments.”

In other words, the missions were the Wal-Marts of Sonora’s seventeenth to nineteenth century. They functioned as remote supply centers where the pantry of Sonoran Desert, local foods like the three sisters of corn, bean and squash as well as wheat, dried beef, and preserves like quince paste were stored for communal distribution and consumption. Many of the by-products of the mission’s food production were also products commercialized for the mining industry. These economic activities have been referred to as the “rendering economies” by archeologist Barnet Pavao-Zuckerman based on her zoological research at mission sites of the Pimeria Alta like mission San Agustin del Tucson and Cocospera. However, the relationship between the mines and missions could also be frequently ‘antagonistic’ in their competitive need for Indigenous labor for their operation. Calorie-rich beef and the useful by-products of the slaughter of cattle such as tallow candles, hide bags for ore, durable leather clothing and tack for livestock and horses were equally important economic products of the missions. Indeed, Cattle was a form of frontier currency, a role can see in the records of Tumacacori mission whose later Fransican Padre Eselteric sold 4,000 head of cattle to a rancher to finance towards the completion of construction work.

BEEF

With the Spanish introduction of cattle to Sonora and Arizona, one of the most important roles of the missions played were their emergence as ranches, a commercial backbone based on livestock ideally suited to the arid Sonoran environment. In his memoir, Pfefferkorn describes the process of elaborating one of the most important finished products of this ranching tradition in the missions, carne seca:

“Now the animal is skinned, the fat and tallow removed, the meat cut into strips, salted, and hung in the sun on stout cords. When the meat has thoroughly dried, it is put aside for daily use. This is the beef which appears every noon on the table; this is the roast; of it, soup is brewed and ragout prepared. In Sonora one can expect no other delicacies. Fresh beef is a rarity and very few can afford to buy mutton. Habit makes everything endurable, and hunger seasons things well.”

This last citation evokes Miguel de Cervantes' quote in Don Quixote that the “best sauce is hunger” and underscores the importance of a non-wasteful approach to vital resources like the harvesting of cattle in a scarce arid landscape.

A fundamental trait to acknowledge when it comes to Sonora’s food culture is its amazing capacity for resourcefulness. This resourcefulness is inherent in Sonora’s emblematic machaca made from carne seca (beef jerky). At the arrival of San Agustin de Tucson’s first resident priest in 1757, the occasion was marked by a good will offering of dried beef distributed by the freshly arrived Jesuit, Bernardo Middendorf who wrote:

“After a campaign of three months Tucson (in Pimeria Alta) was named as my future mission. This place is situated five leagues north of Mission San Xavier del Bac. Some few Indians who had been baptized by Father Alonso Espinosa at San Xavier lived at Tucson among the heathen and the unconverted. It had been decided to found a new mission at Tucson to support and instruct those who were already Christians and to bring others who were not into the Christian belief. I went among them the day before Epiphany in 1757 with ten soldiers for my security. I gave them gifts of dried meat to win their good-will and in this way attracted about seventy families which were scattered in the brush and hills.”

As an example of where food and diplomacy intersect, the origins of the modern city of Tucson can be traced back to this formative act of sharing beef jerky in underlying the importance of food to not only mission history but for the state of Arizona and the Southwest in general.

WHEAT ACCEPTANCE

The essential ingredients to the modern-day carne asada taco or burrito, wheat and beef, first arrived on Sonoran tables at the missions with the arrival of the Jesuits. Because of their significance to mission gastronomy and life, they are often mentioned in their chronicles. These two ingredients have such an important place on the table of Sonora’s gastronomy because of the complementary role these food sources played alongside the native staples of the Sonoran Desert. These introduced foods thrived due to ideal climate and geographical conditions in the region for their developmental expansion. This broadening of the existing pantry of the region with sometimes precarious availability of resources, depending on drought and population pressure, has been called “revolutionary” by University of Arizona Anthropologist Thomas Sheridan, who also acknowledges this despite increased risks as a result of those resources being “target of Apache attacks.”

An example of this revolutionary trend, the socioeconomic ripples spurred on by the acceptance and success of introduced grains like wheat, is in the writings of Juan Bautista de Anza II on his 1774 expedition to California. While traveling along the Gila River near modern Sacaton, Arizona, well beyond the remote missions of Tucson and Bac’s sphere of influence, the Tubac presidio commander noted that the Gila Pima had wheat fields “so large that, standing in the middle of them, one cannot see the ends, because of their length. They are very wide, too, embracing the whole width of the valley on both sides...” This commentary represents the flourishing beginnings of wheat’s successful suitability for cultivation over the winter in the Sonoran Desert beside the summer plantings of the traditional three sisters, its Indigenous production outside mission administration oversight and its importance to the region’s agriculture. Wheat’s role in improving the food security of the region can be attributed to its complementary growing season in the Sonoran agricultural calendar. As a cold season crop it can tolerate the mild winters for development during the time period that it is a winter crop which can be harvested when the traditional indigenous crops as summer season only are planted.

SWEET ENDINGS

To end on a sweet note, one must not neglect the role of hot chocolate played as an imported specialty item in the missions. The importance of chocolate to the early ecclesiatical figures of Sonora and Arizona is underscored by the following anecdote, as related by one of the survivors of the Yuma massacre, the wife of the Spanish settlements via witness testimony:

“Through another Spanish woman captive, who was not with my group, I later learned that Fathers Garcés and Barreneche were not killed until three days later [July 21, 1781]. After leaving the lagoon, the fathers were discovered by a friendly Yuma whose wife was a fervent Christian. He hurried the fathers to his own rancheria, where his wife was waiting.

The enemy fell upon them as they sat in the Yuma’s dwelling, drinking chocolate. The rebel leader shouted: “Stop drinking that and come outside. We’re going to kill you.”

“We’d like to finish our chocolate first,” Father Garcés replied.

“Just leave it!” the leader shouted. The two fathers obediently stood up and followed him.”

Although he was not a Jesuit, Father Garces was a part of the first wave of gray robed Franciscans sent to the Sonoran frontier to fill the missionary vacuum left with the expulsion of the Jesuits.

Photo by Rachael Gorjestani on Unsplash

As a luxury good in the north of New Spain, brewing up a molinillo-whipped, frothy cup of hot chocolate functioned as a pretext for gathering with special visits where news of recent events both regional and global would be shared by travelers with remote and information-starved priests. This conviviality at the table is a tradition known in Hispanic countries as sobremesa. While taking the time to enjoy their last serving of chocolate certainly eclipsed impending death by clubbing for the Franciscan martyrs Garces and Barreneche, the weight of Theobroma cacao’s cultural cache among frontier clergy can be seen even further back in the Jesuit era annual supply requests made by the missionaries to their order’s quartermasters in Mexico City, known as memorias. In the list dated 1736 for Padre Felipe Segesser, resident Swiss priest at the mission of Tecoripa, Sonora, there are twenty-seven different items requested at varying quantities. Chocolate’s placement on the supply list as number one, in the quantity of six arrobas (150 lbs.) of “fine” quality and number two, at two arrobas (50 lbs.) “of ordinary quality,” alongside the requisite third item for chocolate caliente, a “tercio” sized package of sugar, leaves little doubt to the importance of this foodstuff to mission life and hospitality on the Northwestern frontier. Besides the chocolate and the sugar, four pounds of spices - pepper, cinnamon and saffron are the only other non locally available comestible items requested by Segesser for a shipment to last an entire year of mission life.

CONCLUSION

Modern Sonora and Arizona can find its gastronomic origins in the syncretism that developed out of the adaptations of dual cultural traditions connected to food. This syncretism first took place at the mission outposts of the Jesuit order in the region amongst the diverse native peoples with long histories linked to the land. These institutions served as kitchen laboratories, incubators of bringing these two culinary traditions together that led to the genesis of modern Sonoran cuisine. This quality of allowing for assimilation in the cuisine of the peoples of the Sonoran Desert is important to acknowledge. The openness to immigrant cultures and their food culture is not something that only happened into the past and is static it continues on. One just needs to try a Sonoran hot dog at the University of Sonora in Hermosillo or indulge in the classic fiesta plate of barbacoa with frijoles maneados and American style coleslaw or pasta salad.

Works Cited

Brenneman, Dale S. Climate of rebellion: The relationship between climate variability and indigenous uprisings in mid-eighteenth-century Sonora. The University of Arizona Campus Repository, 2004. https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/266813.

Dahlquist, Robert E. A Jesuit Missionary in Eighteenth-Century Sonora: The Family Correspondence of Philipp Segesser. Alburquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2014.

del Río, Ignacio. “Auge Y Decadencia De Los Placeres Y El Real De La Cieneguilla, Sonora (1771-1783).” Estudios De Historia Novohispana 8, no. 8 (1985): 81-98. https://doi.org/10.22201/iih.24486922e.1985.008.3284.

Hu-DeHart, Evelyn. Missionaries, Miners, and Indians: Spanish Contact with the Yaqui Nation of Northwestern New Spain, 1533–1820. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1981. https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/632280.

McCarty, Kieran. Desert Documentary: The Spanish Years, 1767-1821. Tucson: Arizona Historical Society, 1976.

Moraga Campuzano, Guillermo. Comida tradicional del Desierto de Altar. Mexico City: Secretaría de Cultura - Dirección General de Culturas Populares, 2016. https://www.culturaspopulareseindigenas.gob.mx/pdf/2020/recetarios/Comida%20tradicional%20del%20Desierto%20de%20Altar.pdf.

Nentvig, Juan. Rudo Ensayo: A Description of Sonora and Arizona in 1764. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1980. https://web.archive.org/web/20180304080158/http://www.library.arizona.edu/exhibits/swetc/rudo/front.1_div.1.html.

Pavao-Zuckerman, Barnet. "Missions, Livestock, and Economic Transformations in the Pimería Alta." In New Mexico and the Pimería Alta: The Colonial Period in the American Southwest, edited by Douglass John G. and Graves William M., 289-310. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2017. Accessed May 5, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1mmftg6.18.

Pfefferkorn, Ignaz. Sonora: A Description of the Province. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2016.

Rea, Amadeo M.. At the Desert's Green Edge: An Ethnobotany of the Gila River Pima. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2016.

Salmón, Roberto Mario, and Thomas H. Naylor. "A 1791 Report on the Villa De Arizpe." The Journal of Arizona History 24, no. 1 (1983): 13-28. Accessed May 5, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41695699.

Segesser, Philipp. La relación de Philipp Segesser: correspondencia familiar de un misionero en Sonora en el año de 1737. Translated and edited by Armando Hopkins Durazo. Hermosillo: Printed by the editor, 1991.

Sheridan, Thomas E. Historic Resource Study: Tumacacori National Historical Park. National Park Service, 2004. https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/DownloadFile/472836.

Stern, Peter, and Robert Jackson. "Vagabundaje and Settlement Patterns in Colonial Northern Sonora." The Americas 44, no. 4 (1988): 461-81. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1006970.

Treutlein, Theodore E. "Father Gottfried Bernhardt Middendorff, S.J. Pioneer of Tucson." New Mexico Historical Review 32, 4 (1957). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol32/iss4/3.

“San José de Tumacácori.” Tumacácori National Historical Park. National Park Service, June 19, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/tuma/learn/historyculture/tumacacori.htm.

West, Robert C. Sonora: Its Geographical Personality. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993.

Wolf, M.. “Plant Guide for tepary bean (Phaseolus acutifolius).” USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Tucson Plant Materials Center. September 2018. https://plants.usda.gov/plantguide/pdf/cs-pg_phac.pdf.

Yetman, David. "Pedro De Perea and the Colonization of Sonora." Journal of the Southwest 53, no. 1 (2011): 33-86. Accessed April 29, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23337326.

This article was originally shared as a lecture in the XIII Foro de las Misiones del Noroeste de México, dedicated to the Memory of Raquel Padilla Ramos, in May 2021.