The San Francisco Xavier Pilgrimage to Magdalena de Kino

“ San Francisco es un santo muy milagroso, pero a la vez es un santo muy cobrador, y lo que debes, pagas. (Saint Francis is a very miraculous saint, but at the same time he is a saint who exacts his price, and what you owe, you pay).”

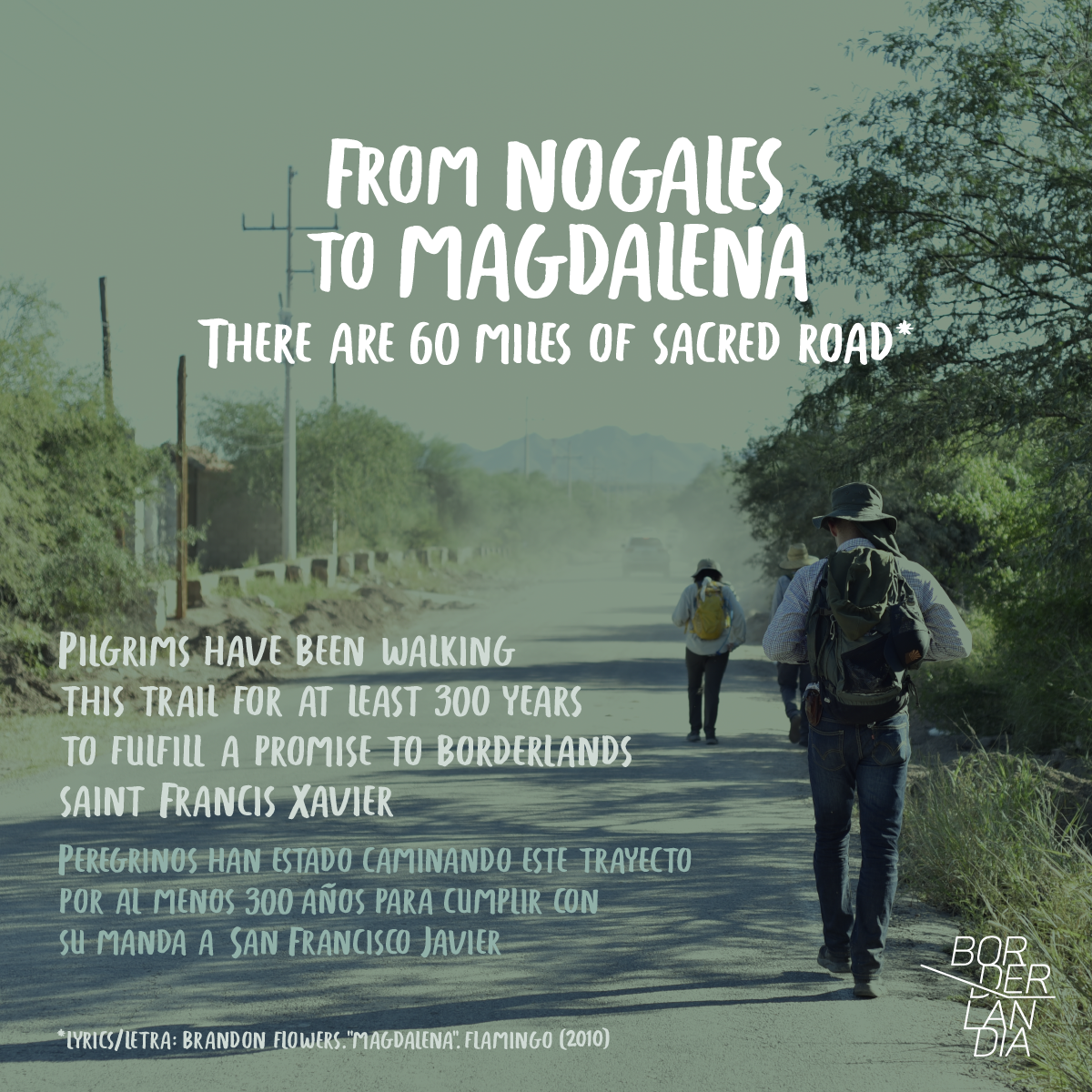

It is said to be a tradition dating back at least 300 years when no border wall or political division existed bisecting the Arizona-Sonora borderlands region. Every year thousands of people representing different cultures walk on pilgrimage to the northern Sonoran community of Magdalena de Kino, Mexico, approximately 60 miles south of the US-Mexico boundary. The pilgrimage terminus of Magdalena is where pilgrims annually arrive on foot or on horseback to visit the popular borderlands saint of San Francisco Xavier in the days and weeks leading up to the traditional feast day of October 4. Typically, after visiting the reclining statue of the saint, the pilgrims also frequently take advantage of being on the plaza in the Sonoran community to peer down into the neighboring crypt of a Jesuit pathfinder named Father Eusebio Francisco Kino. This action of also visiting with Kino is very appropriate given the missionary’s role as the seventeenth-century harbinger of the cult of San Francisco Xavier into the Arizona-Sonora borderlands, an area known in Spanish colonial records as the Pimeria Alta.

This document presents an exploration of this binational cultural phenomenon by first providing brief biographies of Father Kino and patron San Francisco Xavier, followed by a background behind the tradition of the pilgrimage of San Francisco Xavier to Magdalena, Sonora, and finally examining the cultural stakeholders of the tradition and reasons for partaking.

To understand the origins of this tradition, an awareness of an early important Arizona- Sonora borderlands personality and patron saint is key. Eusebio Kino was born in 1645 in the alpine Trent region of Italy but at the time of birth his surname was Chini (the last name was later Hispanicized to Kino) and this birthplace was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Eusebio Kino took the middle name of Francisco as a young man in recognition of Saint Francis Xavier whose intervention he accredited to healing himself during an extreme illness along with the promise of following in his footsteps to become a missionary.

Kino likely looked up to Saint Francis Xavier, one of the founding members of the Jesuit order in the 16th century as the ultimate incarnation of a missionary having reached India and as far away as Japan to evangelize for the Roman Catholic church and performed miracles along the way. Inspired by this example, excelling in Jesuit schools and rising in the ranks of university academia, Kino kept on his promise to become a Jesuit missionary initially desiring to proselytize in China - a goal also originally on the horizon of patron San Francisco Xavier but cut short by the saint’s death on an island just off that mainland. However, when the time arrived to be shipped out to fulfill the work of an apostle, there was only one place for the mission to China but two candidates, Kino and another Jesuit. By a stroke of fate, it was decided that Kino would be sent to Mexico instead of a missionizing post in China. Kino’s adeptness at astronomy and cartography earned the freshly arrived Jesuit a place on a Spanish colonial expansion expedition to Baja California.

Due to a lack of rain for the fruition of crops, the California mission was called off and Padre Kino was re-assigned to what was considered the ‘rim of Christendom,’ the limits of New Spain in present-day northern Sonora and southern Arizona. Kino spent 24 years founding missions in this entire region and forever changing its cultural landscape in the process.

One of the Jesuit’s greatest achievements was discovering that California was one of the longest peninsulas in the world rather than an island as was commonly depicted in maps of the era. Father Kino passed away in Magdalena in 1711 after just completing the construction of a chapel dedicated to his patron of San Francisco Xavier and came to be buried within the small church. Eusebio’s other great achievement was as the region’s first peacemaker between the indigenous and Spanish, potentially the reason that in death, the Jesuit priest came to be honored by members of the Tohono O'odham arriving to pay their respect to the black robe from as far away as San Xavier del Bac mission - a potential origin of this pilgrimage tradition.

The life Eusebio Francisco Kino led and the history he left us as a major figure in Arizona-Sonora history is the cause for inspiration by many and currently the Jesuit missionary of the Pimeria Alta is being considered for sainthood by the Vatican.

An indigenous community called Uquivaba (meaning “high cliff” or “spring”) of a tribe then known as the Pima - and now the Tohono O’odham nation existed along the banks of a life-giving river in the Sonoran Desert. This village is where Kino arrived in 1690 to found Santa Maria Magdalena de Uquivaba as a visita - essentially a sub-mission without a resident priest under the jurisdiction of a nearby mission equipped with a priest called cabecera - in this case nearby San Ignacio de Caborica. The priest stationed in San Ignacio would administer duties such as baptisms, marriages, burials, and masses on occasion at Magdalena along with the other nearby visita station of Imuris.

There is a prominent local legend relating the reason why the statue of San Francisco Xavier, the icon of the pilgrimage, is located in Magdalena rather than the statue’s intended destination of its more northerly namesake, San Xavier del Bac. It is because an incident while in transit to the northern mission curtailed San Francisco Xavier’s journey: when the men carrying the statue of the saint rested in Magdalena and upon resumption of the journey the statue could not be lifted or moved and so since then it has been considered a divine intervention for placement in its present home.

Dating to the Jesuit period in Magdalena, one can still see the cobblestone foundations in a perfect line of the chapel dedicated to San Francisco Xavier within which the black-robed pathfinder was buried when looking down into the crypt in the Kino Memorial plaza. This stone footing is perhaps an indicator of the evolution in the tradition from journeying to pay respect to the deceased Padre Kino buried within the chapel dedicated to San Francisco Xavier to honoring rather the patron saint the black robe brought to the region. Considering the patron of the chapel where Kino was laid to rest was the destination of the earliest of pilgrims to Magdalena and that Padre Kino is still not officially a saint in the Catholic tradition, this could be a logical conclusion.

Another peculiar aspect of the pilgrimage to Magdalena in honor of San Francisco Xavier is that the feast day celebrated in Magdalena (October 4) is not the Jesuit saint’s feast day (December 3) but rather of another saint named Francis - San Francisco de Assisi. This alteration of the date to celebrate the Jesuit saint on the feast day of the founder of the Franciscan order is perhaps directly due to the circumstances of the Jesuit expulsion from Spanish territories in 1768 by the Spanish Bourbon monarchy. Franciscan missionaries may have altered the date in recognition of their order’s founder, who were assigned to the Pimeria Alta to fill the void where their Jesuit predecessors left off due to their sudden expulsion.

Many of the monumental-scale missions that continue to exist today in the region are physical marks of the Franciscan's ambitious building program, influence, and presence. In this way, one can see the layers of history of the region wrapped up in the pilgrimage and fiestas in Magdalena culminating on October 4 and in homage and honor of the trinity of Francis’ - Kino, Xavier, and Assisi.

In a description published in KIVA of the Fiestas de Magdalena in 1967, University of Arizona anthropologist James Griffith organizes the groups and activities of the participant stakeholders in this annual tradition. Big Jim acknowledges three cultural groups present in Magdalena de Kino drawn by the Fiestas: Mexicans and Mexican-Americans, Tohono O’odham from the U.S., and Yaqui and Mayos from southern Sonora. These cultural identities are further broken down by Griffith into roles at the fiestas, that of the pilgrim, the merchant, and the entertainer. Based on the Arizona folklorists' observations, the conclusion he draws on the festival’s 20th-century evolution is that the religious role of the pilgrim and the commercial role of the merchant is frequently merging with the modernization of northern Mexico. However, it appears that the commercial interests are for many indigenous pilgrims frequently practical and secondary to help finance the costs associated with the primary: making the pilgrimage. The Yaqui from southern Sonoran towns like Potam tend to fulfill the role of entertainers - musicians and dancers of traditional Yaqui dances such as the deer dance and pascolas. Neighbors of the Yaquis, the Mayos also perform their cultural dances with music including the harp in and around the plaza of Magdalena.

When asking these varying stakeholders their motivation behind walking the distance to Magdalena, pilgrims will most frequently cite a personal manda. The manda is a promise you make to San Francisco Xavier to come on foot or even on horseback to show your sacrifice for a petition the pilgrim makes to the Saint to intercede on behalf of their request. In return for the sacrifice, the pilgrim-aspirant hopes to benefit from the miraculous spiritual power attributed to San Francisco Xavier in the fulfillment of a particular prayer request.

The current reality that the San Francisco Xavier pilgrimage now spans the breadth of two countries highlights not only a pilgrimage that crosses borders literally but also a crossing of boundaries figuratively. It requires one to pause and reflect beyond modern political institutions like the border with its myriad of agencies and accompanying red tape to think of a time in the origins of this tradition when this all did not exist. Perhaps even more importantly, participation or merely observation in this pilgrimage is a cause for recognition in the unison of common humanity in the struggle for life beyond nationalities given the tradition’s diverse participation. As such, it can serve as a healing example from the region’s history of goodwill beyond cultural borders in aspiration of one day shedding the present era’s militarized environment rooted in the fear of the other, essentially as a counternarrative.

The pilgrimage to Magdalena can also be considered a ritual emulation of the past, rooted in religious belief but also key to the modern identity and traditions of present-day Sonorans and Arizonans of diverse cultural backgrounds. Tellingly, a statue of Eusebio Francisco Kino, one of two statues from the state of Arizona, stands in the National Hall of Statuary in the Capitol building of Washington D.C. in acknowledgment of the Jesuit’s place etched into the history of our nation. With this central position in the national psyche, there may be hope for wider reflection on the example Kino and patron San Francisco Xavier led of crossing borders to peacefully and spiritually interact with different cultures, now manifested by this pilgrimage to Magdalena, and as a legacy for guiding future international relations in the borderlands.

If you’d like to visit this Pueblo Mágico, join us on our next adventure! Click here for more information.

Works Cited

Bahr, Donald M. "Pima-Papago Christianity." Journal of the Southwest 30, no. 2 (1988): 133-67.

Geronimo, Ronald. "Establishing Connections to Place: Identifying O'odham Place Names in Early Spanish Documents." Journal of the Southwest 56, no. 2 (2014): 219-31.

Griffith, James S. Beliefs and Holy Places: A Spiritual Geography of the Pimería Alta. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1992.

Griffith, James S. "Magdalena Revisited: The Growth of a Fiesta." KIVA 33, no. 2 (1967): 82-86.

Griffith, James S. and Francisco Javier Manzo Taylor. The Face of Christ in Sonora. Tucson: Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2007.

Hayes, Patrick. Miracles: an Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Supernatural Events from Antiquity to the Present. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2016. Accessed October 1, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Morgan, Richard J. A Guide to Historic Missions and Churches of the Arizona-Sonora Borderlands, Tucson: Adventures in Education Inc., 1995.

Officer, James, Bernard L. Fontana and Mardith K.Schuetz-Miller. The Pimería Alta: Missions & More. Tucson: Southwestern Mission Research Center, 1996.

Polzer, Charles W. Kino: A Legacy. Tucson: Jesuit Fathers of Southern Arizona, 1998.

Polzer, Charles W. Kino: His Missions, His Monuments. Tucson: Jesuit Fathers of Southern Arizona, 1998.

Raczko, Sergio Gabriel. Favores Celestiales - P. Eusebio Francisco Kino S.J. YouTube Video, 57:33. September 27, 2018.

Taylor, Lawrence J. The Road to Mexico. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1997.

Williamson, George H. "Why the Pilgrims Come." Kiva 16, no. 1/2 (1950): 2-8.